Resources are being landfilled, dumped, or littered at an alarming rate.

2.01 billion metric tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) are generated across the world every year, and the number continues to grow

Approximately one-third of the waste is not managed sustainably. Chemicals and gases leak into our environment and contaminate groundwater, create air pollution, and endanger human health. This harms natural ecosystems, and depletes resources that could be reused, or up-cycled, recycled, or composted.

Mismanagement of waste is harming human health and local environments while adding to the climate challenge. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Linear economy supports massive waste and pollution

Landfills and open dumps waste precious resources and create harmful pollution

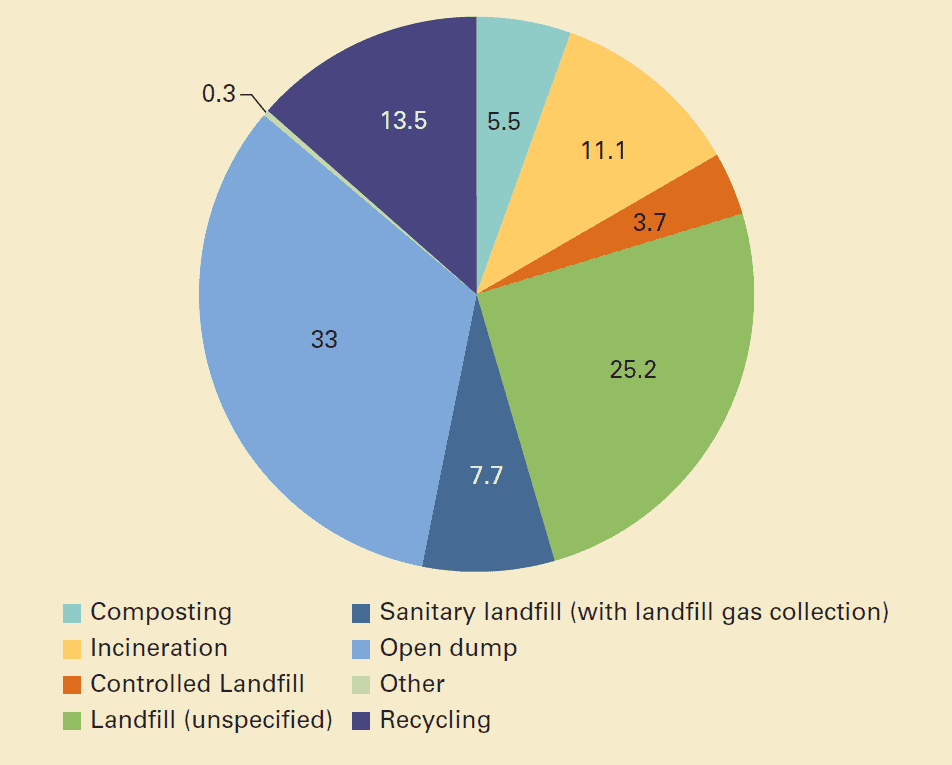

The large majority (70%) of global municipal waste is discarded in landfills and waste treatment centers. This includes organic waste, toxic waste, plastic waste, metal, paper, cardboard, rubber, wood, cement, you name it. The majority of landfills are open dumps or unspecified landfill, of which a very small percentage are sanitary landfills, where greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane are recovered and groundwater is protected. Landfilling offers no recovery of materials whatsoever, yet require enormous investment in order to prevent serious damage to groundwater and neighboring communities.

Incineration and Waste-to-Energy are polluting, costly, and energy inefficient

In the absence of space for landfill, many countries use incineration or “waste-to-energy” as a method for making waste disappear. This results in pollution in each phase of the process: from waste hauling to managing air emissions and residues. Even in the best cases where energy is recovered and toxic chemicals are filtered out, incineration is wasteful. Incineration burns materials which have cost the world precious energy and resources to be created in the first place.

Shipping waste long distances and inadequate waste infrastructure leads to harmful litter

Littering is costly to clean up and toxic to animal and human food chains, habitats and health. It leads to the harmful leakage of garbage like plastic bottles, food wrappers, grocery bags, fast food litter, cigarette butts, plastic straws, and more into marine and land ecosystems. Among other reasons, littering happens when trash is shipped long distances to be disposed of or recycled far away from its source.

The solution? A Circular Economy.

We can adjust waste infrastructure, systems, and habits to accommodate the types of waste we are creating to protect precious ecosystems and save valuable resources. This is the idea behind the Circular Economy. So, what are the benefits and challenges of a Circular Economy?

Recycling is great for cardboard, glass, metal, and paper, albeit very limited for plastics

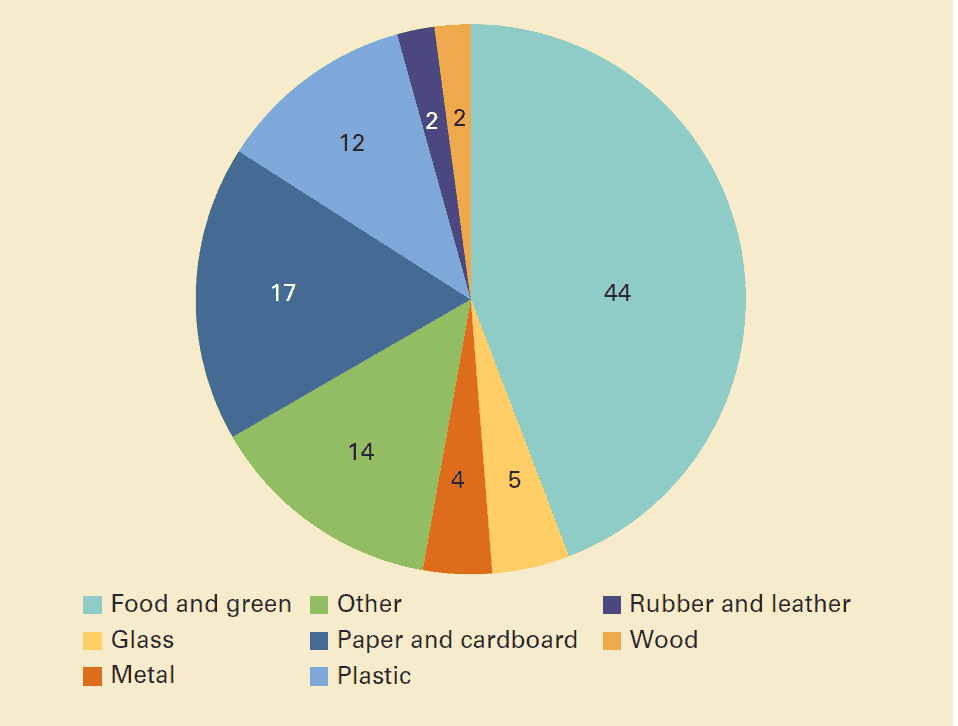

Recycling is an incredibly efficient solution for paper, cardboard, glass, metal, and wood in some cases. Paper and cardboard are highly recyclable and widely recycled and metals like aluminum as well as glass can be recycled infinitely, and these items make up 28% of our global MSW.

As for conventional plastics, which make up 12% of our trash you’ll give your single-use plastic bottle, Ziploc bag, fork, straw, spoon, knife, and shopping bag a longer life by washing and re-using them twice than if you put it in the recycling bin. Plastics recycling has proven largely ineffective, especially in growing segments like flexible packaging, and even if your plastic fork makes it to the recycling plant, it will be melted down and re-purposed maybe once and rarely twice.

Composting organic waste creates healthy, nutrient-rich soil

44% of our global waste consumption consists of food scraps, yard trimmings, and other organic waste, and 17% is paper and cardboard. This means over half of our global waste is compostable—in fact, it means over half of our global waste is home compostable (more on the differences here). Composting is a natural form of recycling where organic matter is broken down into nutrient-rich soil. This can then be used for gardening or large-scale farming. Composting limits landfill waste and methane emissions from organic waste breaking down in landfill and provides nutrient rich compost that nurtures depleted soil.

Compostable plastics like TIPA’s packaging can be composted in organic waste schemes and will break down like a coconut, banana peel or yard waste, and transforms into healthy compost that can then be used for soil regeneration.

(Also see the difference between recycling vs composting in this latest article.)

What does the future look like?

Organizations like The Ellen McArthur Foundation, A Plastic Planet, and Cradle to Cradle are asking the same question, and implementing creative and necessary changes to product design, consumer habits, waste infrastructure and legislation because not all waste is created equal.

“In order to create societies that wastes less—much less, each stream will adopt its own solution,” says Daphna Nissenbaum, CEO and co-founder of TIPA® Corp.

“In order to create societies that wastes less—much less, each stream will adopt its own solution,” says Daphna Nissenbaum, CEO and co-founder of TIPA Corp, signatory of the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment. Daphna, like many others, is confident that composting infrastructure will grow exponentially in the next ten years—which would aid in accommodating the almost billion metric tons of organic waste that can already be sent to compost facilities. She predicts that more compostable solutions for plastic will be available on the market, ushering in a new future for waste that is not wasted.

Technologies like TIPA® have already replaced over 600 tons of conventional flexible packaging, and are outfitting themselves to be viable for the waste infrastructure of the future, where materials are designed with their end-of-life in mind, and recovered or transformed into resources. Reach out to us here!